Post-harvest management

Figure 1. The images illustrate varying shiitake quality from different harvests and post-harvest conditions. Image (A) shows high-moisture, waning shiitakes in refrigerated storage showing oxidation and bruising on the gills due to them being more open and vulnerable to damage. Image (B) shows high-moisture shiitakes in refrigerated storage that were harvested at the fully-ripe stage with the cap still curled under protecting the gills better from bruising. Shiitakes in image (C) at a more ideal moisture level in refrigerated storage that were harvested at fully-ripe stage show only slight oxidation on the gills (off-white color) and negligible bruising; D) ideal moisture level shiitakes harvested at their prime, showing no oxidation or bruising immediately after harvest.

Largely, shiitake is a forgiving type of specialty mushroom, post-harvest. In ideal storage conditions, shiitakes may last 3-4 weeks in refrigerated storage and still be in useable shape. Clearly, some quality loss is inevitable over this period so you should still market your shiitakes sooner than later, but the good storability characteristics of this mushroom species adds to its commercial viability. Post-harvest management principles and practices help maintain shiitake marketability, broaden the amount of time to market your mushrooms, and provide alternative ideas for ways to get as many of your shiitakes sold as possible.

Prolonging fresh mushroom quality, post-harvest

There are several keys to prolonging fresh market mushroom quality from harvest to market. Like most types of produce, harvested shiitakes benefit from being cooled and put into refrigerated storage as soon as possible. Shiitakes can also suffer from bruising on the gills from handling during harvest and storage if too many mushrooms are piled on top of each other (especially on higher moisture mushrooms and mushrooms waning past fully-ripe stage; Figure 1A). Shallow harvest/storage containers also can help protect the aesthetics of the fringing on the cap, which can ultimately help with marketing. In the field during harvest and during transport to refrigerated storage, the mushrooms should at least be protected them from exposure to heating, direct sun, and wind. Coolers or plastic storage bins are accessible options that work as a temporary handling/storage solution during harvest, although it is important that the mushrooms do not stay in non-breathable containers like this for very long. For any longer period of time, shiitakes need to be in stored something that is breathable to prevent condensation from forming, while simultaneously also discouraging excessive moisture loss from the mushrooms. In other words, something that is conducive to very humid conditions, but not wet conditions. For instance, standard paper grocery bags are a simple, accessible, breathable container option that will moderate moisture flux to a degree, but they are not shallow (so not the most space efficient if you want to prevent bruising also), and the mushrooms are still likely to dry out in less than 3-4 weeks if the ambient humidity is not elevated during refrigeration. This is still more favorable than wet conditions, which will lead to rot, which is completely non-redeemable compared to mushrooms that dry out in storage.

Refrigerated storage

Ideal refrigerated conditions are a temperature of ~33-36°F (temperatures below 32°F will ruin them) with relative humidity levels of ~85-95%. In this environment, shiitakes may lose 1-2% moisture per day in storage, which is not only important for market quality, but also for retaining market weight. If you just starting out at a smaller scale and do not already have a larger, humidity-controlled, refrigerated storage space specifically for keeping produce, a more accessible option would be to purchase a secondhand household refrigerator (or a few, depending on your production size) but there are some important caveats to be aware of. In standard refrigerator, the cooling process is also a drying process, so sub-optimal relative humidity is a concern. One exception is the crisper drawers, which are designed to retain a more humid environment like this by simply reducing the amount of airflow inside that space relative to airflow in the rest of the fridge space. With these types of refrigerators there are a few do-it-yourself options that you can use to modify the humidity levels while the mushrooms are in storage. These include:

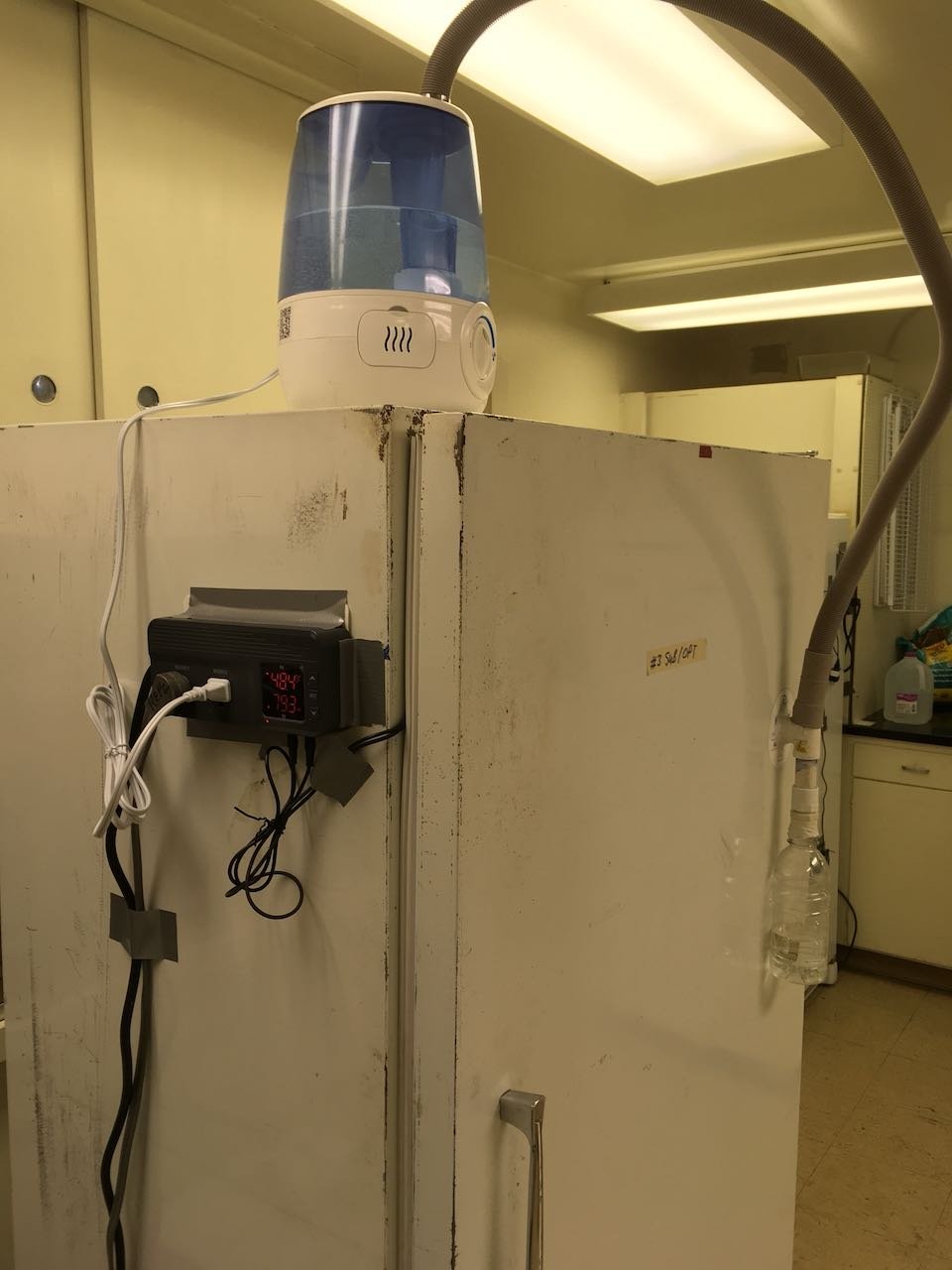

Figure 2. The image shows a secondhand household refrigerator that has been retrofitted to have precise relative humidity control with an external humidifier connected to a humidistat. Although it requires a degree of resourcefulness and ingenuity, a simple fabricated setup like this can be an accessible way to get an optimized post-harvest refrigerated shiitake storage setup on a budget.

Loosely draping plastic over your mushroom containers that are otherwise breathable. This is a rather crude way of reducing airflow around your mushrooms, similar to what a crisper would do.

Placing a long thin tray (or multiple trays) into the fridge along with a wetted, absorbent type of fabric such as terry cloth or other absorbent, spongy material spread out across the tray that can act as a moisture “wick”. The extra moisture that will be emitted from the wick into the air will compete with the drying process that occurs from cooling.

Using a saturated salt slurry to moderate relative humidity to a certain level. A pasty mixture of table salt and water can be spread out over a broad pan and placed in the fridge to maintain relative humidity levels up to 75%. This method of using salt slurries is commonly used in research settings to maintain specific humidity levels in closed chambers. In a refrigerator, this method should work best when the fridge has a circulating fan (some older fridges may not), or a fan placed inside to help circulate the air. As long as the slurry remains saturated, the humidity should be held stable around 75%. Other salts can also be used for targeting different humidity levels, but table salt is the most accessible option to at least get humidity levels closer to the ideal levels. Potassium sulfate (“sulfate of potash”) is likely the next most accessible salt that can be used this way, as it is a commonly used fertilizer that should also not compromise any certifications for growers who are Certified Organic. Saturated slurries of potassium sulfate are capable of maintaining relative humidity levels of ~97%.

Putting an ultrasonic-type humidifier (because it does not use heat to vaporize the water) directly inside a fridge, or retrofitting a standard humidifier’s output to be piped into a refrigerator fridge directly. A 110v AC (i.e. one with a plug-in outlet) humidistat can also be added to either setup to maintain very specific humidity levels (Figure 2). These options may incur some tinkering and ingenuity but for some, it may be worth the effort to have a more controlled system.

Simple thermometer/hygrometer combination gauges are affordable and will allow you to make sure your temperature is set correctly and to monitor whether your method of modifying humidity is working. Any water added to the refrigerator, whether through humidifiers or otherwise will need to be monitored and replenished accordingly. Also monitor to make sure condensation is not developing to in a way that could lead to dripping or pooling water getting into the mushroom containers. Adding a small circulating fan (or several) may help prevent condensation. Also be aware that your refrigerator is not designed to have a high humidity environment like this all the time, so your modifications should only be used when mushrooms are in storage to prevent excessive strain on the refrigerator components.

Grading

Figure 3. The image shows a market advertisement for a specific type of dried shiitake mushroom market class in Japan. A market class like this may be limited to more traditional asian markets. This mushroom class (“Donko”) values forest-cultivation, a thick, fleshy cap with “flower”-like cracking patterns and a distinctive aroma produced by dry, cool growing conditions (late winter/spring), and harvest before the veil of the mushroom opens (i.e. slightly underripe, early waxing stage). This market class would be difficult to produce in the PNW environment largely because simultaneously dry and cool weather conditions are uncommon. Image: Rakuten.com

Whether or not you decide to grade your mushrooms into different market classes will depend on your specific market, and/or whether you determine it could benefit your business strategy. Some markets may be glad to pay a premium for simply being able to get forest-cultivated shiitake mushrooms at all. Others may not. Preferences may also change over time. If your market is more traditional Asian they might be more discerning and desiring some more specific market classes (particularly certain dried shiitakes), some of which may be difficult to provide (Figure 3). Otherwise for domestic markets, you can consider grading into two or three core market classes, largely related to stage of harvest ripeness (Figure 4), or alternatively, grading by size or general moisture content. Harvest ripeness and moisture content grading primarily relates to general mushroom quality aspects, while size grading relates more to targeted uses by a specific market.

Two market classes based on harvest ripeness: Mushrooms whose cap edges are still rolled/curled inward (from early-waxing to early-waning of the fully ripe stage) and would go into an “A” class, while those that have a cap edge that has begun to turn/roll outward and upward (mid to late waning stage) would go into a “B”-grade class.

Three market classes based on harvest ripeness: Mushrooms whose whose caps are still relatively thick and with edges that are still substantially rolled/curled inward (waxing portion of the fully-ripe stage) and would go into an “A” (or “premium”, “fancy”, “Koko”, etc.) class, mushrooms with caps that have begun to flatten but still have edges that are at least still rolled/curled downward (waning portion of the fully ripe stage; see Fruiting & Harvest page Figure 5C) would go into a “B”-grade class. All other mushrooms those that have a cap edge that has begun to turn/roll outward and upward (mid to late waning stage), would go into a “C”-grade class.

Two or three market classes based on size: Mushrooms may be divided similar to how other types of produce are classified with Large, Medium, and Small grades, or just Large and Small. The decision to grade by size laike this will largely depend on the preferences expressed by your specific market.

Alternative “A” grades could be mushrooms with exemplary aesthetic qualities, clustered mushrooms (multi-stem), exceptionally large (“griller”) or small (“baby”) mushrooms (depending on market preference), slightly underripe mushrooms (where the cap has expanded substantially but the veil has not broken yet, e.g. “Donko” grade in Japan), and mushrooms with a more ideal moisture content (see figure 1C and D) . Alternative downgrading to “B” or “C” grades could include misshaped mushrooms, exceptionally large or small mushrooms (depending on market preference), or mushrooms that have a high moisture content (see figure 1C and D), or have physical damage (ripped, bruised, etc.).

Mushrooms that should be culled are those that have come into contact with a potential fecal-oral contamination pathway, mushrooms with pest damage, and/or any other other contaminants compromising food safety. Other mushrooms that are safe to eat but have significant quality compromise, including wet mushrooms from exposure to rain, overly desiccated mushrooms from exposure to wind, and mushrooms that have sporulated or have been sporulated on, should also be culled to avoid putting your market reputation at risk. See the Fruiting & Harvest Gallery page for visual examples of non-marketable mushrooms.

Figure 4. The figure provides examples of the generalized spectrum of a two-tier and three-tier shiitake market class grading system based on harvest ripeness stage. The image of the mushrooms shows the relative openness of a range of mushroom caps and the cap edge, two defining factors in determining harvest ripeness which generally correlate with shifts in mushroom quality and market weight. The other determining factor which can’t be seen very well in the image is the relative thickness of the cap. What can be seen in common between the two systems is that the lowest tier/grade is centered around the waning stages of maturity after full ripeness ends but before sporulation has occurred.